In resuming blogging I first surveyed my files and g(l)azed over notes I had made for what could have become a post published at the end of October, entitled “Keeping it real. Or: a few desultory thoughts upon a surprise nexus formed subsequent to the viewing of two new biopics and the same-day chancing upon an article on dubbing practices in the Czech Republic.”

Yikes.

The biopics in question are Gainsbourg and The Social Network. I reviewed them both on 3RRR's “SmartArts” as far back as October 28 and I can't say I now feel half as interested in writing anything much about them as I seemingly did back then, even if, from the title of that abortive effort, I was only aspiring to wax desultory upon them in the first place. Perhaps nothing more had been at stake than an elegant segue... into something I had really wanted to pontificate about: the dark art of dubbing. (About which, finally, a little more below.)

The here and now: firstest things first

One of the things keeping me from blogging was a very tight deadline for laying out the latest issue of Screening the Past, a special issue focusing on “Cinema/Photography: Beyond Representation”, guest edited by Des O’Rawe and Sam Rohdie. Were that the deadline hadn't been half so tight; I hadn't a show of writing my promised review of William Beard's Into the Past: The Cinema of Guy Maddin in time. Nevertheless, there's sure some mighty fine reading (and viewing!) there people – get to it! And I'm sure my review, come a relaxation of time constraints, will smuggle its way into the next issue of STP.

On the matter of venerable Melbourne-based online film journals, let me record here my utter dismay and astonishment that Screen Australia has pulled ALL of its funding of Senses of Cinema, that online film journal of possibly unparalleled international renown, esteem, contributorship and readership, in a decision which, for mine, speaks great, vacuous, parochial volumes about what the nation's premier screen cultural funding body values in terms of contributions to Australian screen culture. The near-sightedness of this decision is breathtaking in all its gormlessness. I am flabbergasted.

I have long enjoyed a strong affiliation with Senses of Cinema, having previously, as the site's designer/administrator over eight or so years, slaved away over the mark-up and illustration of literally hundreds of superbly researched and written essays, book and DVD reviews, annotations for the Melbourne Cinémathèque, Great Directors profiles, and film festival reports, along with having contributed no few festival reports myself (along with, in a former guise, a strangely hyper-real “bricolage interview” with a certain Richard Wolstencroft – may the ludicrous business surrounding his house being raided by the police looking for copies of L.A. Zombie, two whole months pursuant to a widely publicised and uneventful civil disobedience screening of the same, resolve itself with the barest minimum of juridical intervention).

While I am no longer on staff at Senses (albeit I am still doing some work for it, migrating archival content into Senses' spanky new content management system), I still personally feel this grotesque, and conceivably crippling, slight against this wonderful journal, profoundly. I hope many others out there, readers and/or contributors alike, will, on this news reaching them, feel similarly appalled. Oh if only, somehow, the collective umbrage of all the world's cinéphiles could somehow be monetised...

Now, where was I?

Oh yes.

Well, bugger that business about the biopics. Let's move straight onto the dubbing practices in the Czech Republic... Although... perhaps... not until I've given a further account of things of interest to have occupied me between blog posts.

Max and Moritz: A Juvenile History in 7 Tricks (Minus 3)

|

| Penelope Bartlau, Megan Cameron, Moritz and KT Prescott in Max and Moritz. Photo by Sarah Walker. |

... a quite deranged expanded marionette theatre production of most of Wilhelm Busch's 19th century tale of a couple of very naughty boys who just might get what's coming to them – and how! But not before certain entertaining unpleasantries might first come to pass...

... under the direction of puppeteer extraordinaire Megan Cameron and with no small amount of on-stage shenanigans courtesy of the same, in cahoots with KT Prescott and Penelope Bartlau...

... with musical accompaniment from Dirty Nicola and the Cheap, Filthy, Pre-Loved, Shop-Soiled Spud Hussies (myself, Katrina Wilson & Nicola Bell).

|

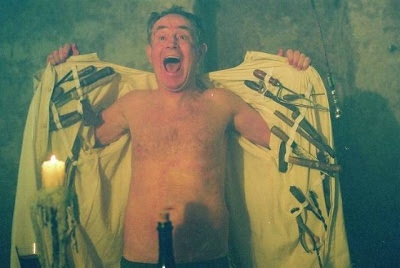

| Shop-Soiled Cerise BRINGING IT during Max and Moritz. Photo by Sarah Walker. |

(Now here's a hot tip: If ever you'd been wondering how best you might simulate the sounds of children being ground to a pulp in an old mill, might I be so bold as to heartily recommend the strained employment of an egg-beater against several clumps of cement in an ice-cream container?)

For all its wonderful reception, I can imagine that the spectacle our Max and Moritz provided might well have bewildered some of its audience. Some of that might have been a function of our presenting this as very much a work in progress, and as such, a little rough around the edges. Another part of it might have been that eyelines to the stage weren't uniformly excellent, something quite important when some of the performance is presented in miniature – oh for tiered seating in future! But, most of all, our Max and Moritz was presented after a very European tradition of marionette theatre – a quite Czech approach to things, in fact. It's a mixed-media, multiple-representational, collage tradition little known around these parts.

My introduction to this sort of theatre came through the cinema of Jan Švankmajer, especially those films of his where the protagonists inhabit a universe wherein they, or any other given character, may oscillate between being (portrayed as) a living, breathing, thinking human being, or a puppet, whether a miniature model or of life size, in the process collapsing distinctions between representation and actuality, autonomy and manipulation, the natural order of things and the fantastical, all in accordance with the time-honoured synthetic Surrealist tradition. See, for example, Něco z Alenky (Alice / Something from Alice, 1988); Don Šajn (Don Juan, 1969), and especially, Lekce Faust (Faust / Lesson: Faust, 1994).

* Note to self: at some point when writing extensively on Švankmajer on future, note that all too little has been written (at least, in English), even by the great Peter Hames, on Švankmajer's involvement in Prague's Laterna magika expanded cinema, with especial respect to his part in creating Kouzelný cirkus (Wonderful Circus), a staple of that theatre's repertoire ever since its premiere in 1977. Here's a promo clip that does a fine job of demonstrating the multimedia, collage approach to theatre/cinema as expounded by the Laterna magika:

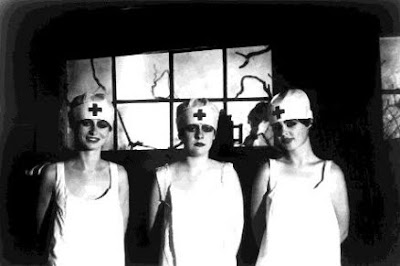

My dear friend Megan Cameron, whose wonderful brainchild Max and Moritz is, developed a lot of her formidable Czech marionette theatre chops from a couple of long stints working in Prague with Divadlo ANPU. Here's a photo I'm very fond of I took earlier this year of Divadlo ANPU rehearsing a new production; I think it illustrates very nicely the multi-layered and interpenetrative nature of representation, characterisation and indeed framing freely employed in this brand of theatre:

The more exposed I've become – as spectator and, latterly, in the case of Max and Moritz, as participator – to this sort of theatrical production, the more some extremely bizarre aspects of Jan Švankmajer's cinema have come to seem, if not so much any less bizarre, at least somewhat more explicable. All that business in Faust playing with an indistinction between a human order of being and a supernatural/puppet order is these days a good deal clearer to me as not simply whimsically Buñuelian, Brechtian or post-modernist manoeuvring on Švankmajer's part but at least equally an adherence to venerable Czech theatrical traditions in which representation is ever a slippery and unstable business indeed!

And then I went to Wellington

(If only, alas, for just a few days.)

Wellington's where, back in the day, I was a) born and b) spent many of my formative years, and I had been away from it for way, way overlong. The hows and whys are not the stuff of this blog, but a few choice snaps taken, methinks, are. Whose blog is it anyway? Yes, that's what I thought too.

Scenes from the 2010 Wellywood Collection

|

| But one third of the spectacular view from the back of my Aunt's place in Wellington. |

|

| Why would you watch TV? |

|

| I sat here on the beach at Lyall Bay, making light work of a first paua fritter in 10 years, watching the planes come and go. Skull Island scenes from Peter Jackson's King Kong were shot nearby. |

|

| Colonial timber houses tumbling down the hillside at Lyall Bay. A whole different approach to terrace housing. |

|

| The Beehive, on the prowl, Dalek-stylee... |

|

| On the Cable Car, heading up to the Wellington Botanical Gardens. |

|

| Henry Moore's Inner Form, enjoying the view from the Wellington Botanical Gardens. |

|

| Gorgeous Second Empire building in Wellington's CBD. |

|

| This CBD Art Deco stunner is for sale! Will some kindly soul not buy it for me? |

*

In “Arty Bees”, a wonderful Wellington vendor of pre-loved books, I stumbled upon the find of my too few days spent in the Windy City: Gene Deitch's wonderful memoir For the Love of Prague (2nd edition – there have now been five).

It's the memoir of a man uniquely placed to observe and comment upon the experience of living in communist Czechoslovakia for 30 years; Deitch, an animation producer – a UPA alumnus, no less – was the only American resident in Prague throughout 30 years of communist rule (and beyond! When originally he'd intended to stay for no more than 10 days...) Deitch enjoyed considerably more freedom of movement and considerably less harassment by the state than the rest of the population, bestowing upon him a privileged position both in society and as a documenter of communist Czechoslovakia's everyday, absurdist drudgery and, eventually, the seismic events that proved the regime's undoing, ever the outsider, looking in...

As a Czechophile, that's already premise enough to have got me interested in his memoir, but the jackpot is that Deitch's book also recounts his time overseeing production of cartoons, including an Oscar winner (Munro (1960)) and numerous Tom and Jerries destined for the American marketplace, created by workers in none other a studio than Bratři v triku (“Brothers in T-Shirts”, but, equally, “Brothers in a Trick Film”), the Prague animation studio founded in 1945 by none other than legendary Czech puppet animator, Jiří Trnka!

One passage early on recounts how Deitch, before becoming acquainted with his new workmates, had been naïvely fearing the worst, conditioned by American propaganda to expect them to be a bunch of humourless, party line-toeing drones toiling away mechanically and unemotively at their work; it couldn't help but remind me of the fancifully draconian production line approach to creating cels and merchandising for The Simpsons as envisioned by Banksy as occurring in China in his recent Simpsons title sequence that many of you would have seen by now:

I can't say enough wonderful things about Deitch's memoir. Of course, I now desperately want to get a hold of its most recent edition – I'm three behind. Until I do though, there is “The Occasional Deitch” online to tide me over and... a feature-length documentary film adaptation of his memoirs to also hunt down!

Finally: a few musings on the practice of dubbing

An article from 2008 I stumbled upon recently on the website for Radio Praha, “The continuing Czech love affair with Jean-Paul Belmondo”, considers the enduring appeal in the Czech Republic of a French actor not greatly well known these days beyond France outside of cinéphile circles (within which, of course, he is revered, especially for his roles in Godard's A Bout de Souffle (Breathless) and Pierrot le Fou). What for me makes this especially interesting is that, as this article would suggest, there is a high likelihood that most of his Czech fans have probably never actually heard Belmondo speak – at least, not in his own voice.

(Instead, one of the two actors known to have been his voice for Czech audiences throughout Belmondo's career is none other than Jan Tříska, so brilliant as the Marquis in Švankmajer's Šílení (Lunacy).)

|

| Jan Tříska in Šílení |

One essential element for anglophone audiences in the construction of star personae in the Hollywood system is, of course, voice. It is very rare – outside of the conspicuous or mannered adoption of an accent or some sort of speech “impediment” – that a star's voice isn't recognisably the same from one role to the next. We pretty well take it for granted – I doubt any of us ever rarely spare the matter much thought at all – that an actor, already familiar to us, will sound much like he/she always does when we go to watch them in a new role. Likewise, we take it for granted that their lip movements will reliably synch well with the dialogue on the soundtrack.

Throughout much of Europe, however, including the Czech Republic, local voice talent is often employed to dub the dialogue in foreign films, for theatrical release and for television. In these cases, wherever established actors are involved, there are particular local actors assigned as the voice of those stars. This consistent assignation of voice to foreign star no doubt helps cultivate, and by degrees, cement, those stars' personae within those marketplaces; otherwise, just imagine how weird and distancing it would be to hear Sean Connery dubbed by an appreciably different voice every time you saw an old Bond film.

But then... imagine never even realising that Connery himself has one of the most distinctive voices on the planet, with that rich, thick Scottish brogue so beloved of parodists throughout the anglophone world!

I wonder how often Hollywood stars meet their matches? Has Brad Pitt ever met the Spanish Brad Pitt? Has Angelina Jolie the German Angelina? What would happen if ever Belmondo and Jan Tříska were cast together? Perhaps they could dub one another - in many nations, who would ever be any the wiser...

That's enough for now

Chances are the next post to A Little Lie Down will come rather sooner than this one did. Meantime, I'll be joining Thomas Caldwell on this Saturday's Film Buff's Forecast on 3RRR, midday-2pm. Tune in! Turn on! Etc.